|

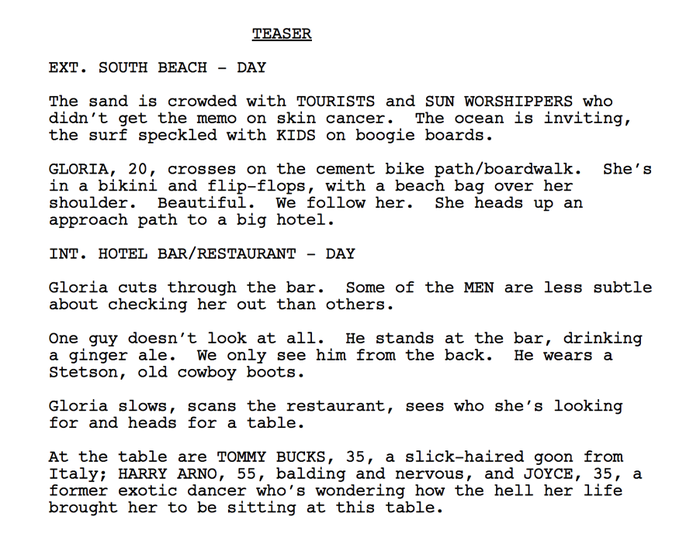

by Marla White It would seem self-evident that the script’s #1 priority is to engage readers. Sure, visuals are great and all, but so many scripts I’ve read spend more time focusing on “CU of wheel” and “Pan to open door” and less time on actually being an interesting written document. Fun fact: reading a script that starts every sentence with either a pronoun or a character’s name is a faster way to fall asleep than Tylenol PM. Okay, that’s not entirely true, but it’s boring to read and it has to be boring to write. Just stating what happens in a scene isn’t enough; facts are dry and lifeless. Take a look at this example: Nancy hears a knock at her door. She gets up and answers it. She’s surprised to find BETTY standing there. Betty barrels into Nancy’s apartment. BETTY Thank God you’re home, I didn’t know where else to go. Nancy shuts the door. She turns to look quizzically at Betty. NANCY I’m sorry, who are you? You get the idea. It describes the action in the scene, but in the dullest way possible. Think how much more appealing it would be to keep reading this script if it went something more like this: There’s a pounding at Nancy’s door. She bolts up out of bed – it is three in the morning after all, where else would she be? Making her way through her apartment, stubbing her toe along the way, Nancy yanks the door open. Staring bleary-eyed back at her is her BFF from high school, Betty. Reeking of alcohol and desperation, Betty pushes her way into the apartment and bonelessly flops on the couch. BETTY Thank God you’re home, I didn’t know where else to go. Nancy looks up and down her apartment hallway. Is she being punked? Hesitantly, she closes the door but keeps her hand on the knob, ready to bolt. Eyes wide as saucers, she stares at her guest. NANCY I’m sorry, who are you? To be honest, my friend the grammar snob (no seriously, that’s her website, she’s written books about grammar) would ding the second version for having too many introductory sentences. Still, you get the picture. The first version tells the same basic facts; the second does it in a way that makes it easy to visualize the scene in your head while you’re reading. It doesn’t matter if it’s a CU of Nancy or pan as Betty walks in because everyone who reads it will picture it differently and that’s ok. If you want a MUCH better example of eloquent prose in a script, here’s a snippet of the first page of the pilot of “Justified” by the great Graham Yost. (thanks la-screenwriter.com!) This is NOT a writer who settles for stating just the facts. Also, in case you missed it that was a super slick introduction of the main character, Raylan Givens.

Take a look at your pilot scripts – do they visually pop as much as they should? Get a free evaluation of the first page of your script to be sure!

2 Comments

|

Marla WhiteCoaching writers who are ready to bring their pitch or script to the next level. Archives

September 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed